Yesterday, I listened to, and forwarded to Ran a talk by Bruce Sterling at this year’s south-by-southwest. Sterling (aka Chairman Brucie) is a subtly infectious thinker- along with his classic cyberpunk writing and advocacy he has also dropped little cultural interventions like the PDF-only White Fungus or Taklamakan and the character of Leggy Starlitz, all of which have tumbled about in my brain since I first read them. He also has a creepy habit of being right about things: his Reboot 11 speech resonates seven years later, for instance, as a description of life in the 20-teens.

Sterling’s latest talk is panoptic and wandering, like pretty much everything else he ever produces, and it hasn’t been transcribed yet (I don’t have time!) but it has a few standout moments. He talks a lot about the dynamics of failed states, for instance: generally, they want to be respected as states, and they can dress themselves up in the costumes of states, but they’re unable to ensure the exclusive right of force within their boundaries, they can’t provide meaningful services to populations, and most importantly, they can’t respond to the people the think they want to serve. There’s no participatory point of entry- they sort of exist, and people sort of negotiate their lives around them, but it comes down to the old Soviet “we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us” which Sterling glosses as “we pretend to govern, and you pretend to pay taxes.”

He links failed states to the concept of the “surveillance state,” one in which the putative government relies on information about the population- preferably, total information about the population- in order to guide its interventions towards whatever its goals may be. This is a hip topic now, as people are realizing (again!) that it is possible to track and influence people without a court order simply by determining what people do and don’t see. Again, this isn’t new.

What Sterling points out is that the surveillance state is, by any measure, a failed state. Despite the Orwellian predictions of a post-wikileaks post-Snowden world, data-driven surveillance and control really sucks as a method of government. It just doesn’t work- for all we complain about Apple or the NSA tracking our phones, there are entire populations where literally everybody has a satellite, a Persistent Surveillance System or a drone following them at all times, and they are (among) the least controlled, the least served, the least governed people on earth. Quoth The Chairman: “Is there anyone with a drone over their head who is actually doing what guys with drones want?”

This is fascinating because the move towards a surveillance state seems completely irresistible. The talk refers frequently to social psychologist and philosopher Shoshana Zuboff (who wrote the “track and influence people” article linked above) whose famous third law states that any technology that can be used for surveillance and control will be. This explains a lot- the FBI and Apple are actually converging on the same status.Both are data-driven control systems that can’t quite claim legitimacy or respect, and neither one has any real influencing ability beyond their capacity to make a few individuals’ lives hell at any given time. In fact, Sterling places Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and the US government in the same failed-surveillance-state category. All are fundamentally undemocratic despite their best intentions, all unable to provide the actual services people want, all focus their energies on collecting data about their constituents, and all exercise control through webs of weird, incomprehensible legal snarls that make no prima facie sense and end up being lawyered out to the point of absurdity. Also, all fancy themselves diplomatic powerhouses.

Wait, the title of this entry was…

So that was my thought last night. Then this morning, I got the news from Belgium along with everyone else and because Bruce Sterling is such a good writer, I started hearing everything coming over the Beeb in the context of a failed surveillance state. You see, there are lots of theories as to why the Middle East is blowing itself up and declaring war on The West and I can’t quite buy any of them. We’ll just discard the racial/cultural/”these people just aren’t ready to be free” crap out of hand, and move on to the slightly more comprehensive. Is this a legacy of colonialism? Somehow no. The Kuwait war clearly was. The “Great Game” in Afghanistan continued well into this century as a colonial (i.e. not even “post-“) conflict without a doubt. But the Islamic State seems to be as much within the west as it is a resurgent nationalism, or opportunist regional resource grab, or other classic power struggle played out in the formerly colonized world. The Islamic State is a creature of the twenty-first century, not the twentieth or the nineteenth, and it reflects the deracinated, globalized, cosmopolitan world in which it arose. It may even be a critique of it- in fact I think it is.

So that was my thought last night. Then this morning, I got the news from Belgium along with everyone else and because Bruce Sterling is such a good writer, I started hearing everything coming over the Beeb in the context of a failed surveillance state. You see, there are lots of theories as to why the Middle East is blowing itself up and declaring war on The West and I can’t quite buy any of them. We’ll just discard the racial/cultural/”these people just aren’t ready to be free” crap out of hand, and move on to the slightly more comprehensive. Is this a legacy of colonialism? Somehow no. The Kuwait war clearly was. The “Great Game” in Afghanistan continued well into this century as a colonial (i.e. not even “post-“) conflict without a doubt. But the Islamic State seems to be as much within the west as it is a resurgent nationalism, or opportunist regional resource grab, or other classic power struggle played out in the formerly colonized world. The Islamic State is a creature of the twenty-first century, not the twentieth or the nineteenth, and it reflects the deracinated, globalized, cosmopolitan world in which it arose. It may even be a critique of it- in fact I think it is.

I have meant, for several years, to write an argument against GMO crops. Not because they are or aren’t dangerous for consumers (I’m more interested in the question of farmworker safety) but because of what they represent to farmers. GMO crops do not exist in isolation- the same companies that produce them also produce the associated amendments and treatments, sell insurance packages, and manage elevator and commodity markets, so that any farmer in a market where GMOs exist is trapped in a net of conditional subsidies, market adjustments, legal liabilities, futures contracts, and other intangible constraints that make it virtually impossible to reject the seeds or the terms of sale. Worse, like Comcast subscriptions and payday loans, the nets of contracts and regulations are intentionally obscured and complex, exposing any would-be dissident grower to legal or criminal action by any entity with better lawyers, which in real life means the companies that produce the seed. There are even rumours about One Particular Seed Company: if you are a local rep or preferred customer for them, and you covet your neighbor’s ground, they will cheerfully sic their legal team on them using all the fine print at their disposal to bring your neighbor to his knees and ensure you pay a low price at the inevitable auction. The ostensible reason for this is the legal framework of intellectual property- all this exists to protect the labor and investment of a few thousand biologists somewhere- but the actual reason has more to do with Zuboff’s Third Law above.

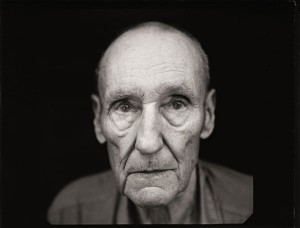

And this is global- thanks WTO/NAFTA/FTAA/TPP/ETC!- and it comes from the country that once distributed the Green Revolution. Say what you like about the Norman Borlaug and the oil markets that inevitably followed him, he fed a lot of people without entrapping them in this kind of crap- but that was when the West had a brand to uphold, the Alternative To Communism, the World of Plenty, a sociological product package that was carefully vetted, improved, developed, calibrated, and essentially made as valuable as possible to our friends. Now that the cold war is over, however, we have intellectual property restrictions and facebook’s Terms of Service. I am inevitably reminded of William S. Burroughs heroin-as-capitalism metaphor:

“The junk merchant doesn’t sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and simplify his merchandise. He degrades and simplifies the client.”

And that’s what we offer the world. Something you think you can’t do without, but which comes with an inherently extortionary involvement with a surveillance-and-control system that thinks it’s a state. Several of them actually- and don’t give me that “golden rice will save children/facebook created the Arab spring” excuse bullshit either. The West no longer makes the world better, the West closes off alternatives. That’s the Western brand.

Does it work?

But as Sterling pointed out, surveillance states suck. Not just ethically, not just as a consumer experience, surveillance states suck at governing, surviving, sustaining themselves, growing.. basically doing any of the things a state should probably think about doing. The classic nightmare state is East Germany, which for all its depth of surveillance, wiretapping, informers’ networks, interrogations, and terror, lasted only one year longer than the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. When the wall finally came down in Berlin, at least a third of living East Germans were older than, and outlived, their own country.

If surveillance states can’t actually guarantee security (or roads, bridges, health care, migration, economic mobility, equitable policing, …) they do seem to be able to piss people off, and also, weirdly, to atomize resistance activities. Sure, facebook can catalyze large-scale uncoordinated actions, but it also seems to impair the structural development of movements. In truth, social movements are easy to break apart, using the same data-driven tools we think we can use to build them. The Islamic State is described as being a social media nation, but in fact its resilience where so many others have collapsed (the April 6th movement, for instance) comes from its very selective use of social media, and its primary reliance on actual social networks of people who know, meet, and give orders to each other. Unlike the twitterati, the Islamic State is willing to go offline and use established leaders. In fact, I think, the temptation to be offline- to be outside the network of legal precarity, debts, terms-of-service, arbitration-only contracts, intellectual property lawsuits, patent trolling, and other exploitative forced choices- is the primary appeal of organizations like IS- or individual actions like walking around with a firearm shooting your coworkers and neighbors.

It works, too. A few determined freedom fighters/terrorists who don’t carry phones, use facebook, or appear in face-recognition databases are completely unstoppable. Even people who are known seem to be hard to stop. What can you actually do to someone with a bomb strapped to their belly? I mean, you can kill them, then they blow up, then they’re dead. Or, you can not kill them, then they blow up, then they’re dead. You can destroy their family’s housing, the way Israel does, or try to embarrass them on social media, the way the US and UK do in their “deradicalization” programs (worthy of another post, those), but you can’t really take anything away from someone who’s already determined to die. You can offer something positive to people who stay alive, but we don’t do that anymore- its not as tempting as punitive control.

Essentially, IS and the assorted mass shooters of North America have hacked the critical flaw in the surveillance state. It offers nothing in terms of narrative, no meaning, no identity, no collective self worth participating in, no compensatory opportunities, just an addiction that knows everything about you. Even that’s only available as long as you don’t, say, want to move to Germany. Anyone wanting something better than this needs only sneak behind the curtain and see that it only functions when people can be deterred by lawsuits, jail time, or police bullets. When people, in other words, have more than a status update to live for.

Bringing it Home

To be honest, I’m not as worried about ISIS as you probably think I should be; like most telegenic horrors its much less relevant to my life than car accidents or heart disease. I am a bit worried about Donald Trump, though, who makes up the other major topic of Sterling’s talk. To hear Sterling tell it, Trump is an American Berlusconi– a comical sort of reality-show replacement for the “face” of the political system, able to absorb the blame for the failures of the deeper machinery but not implicitly a threat. I’m not entirely sure about this, because I think that Trump, and his supporters, many of whom I live and work with, have clued into something similar to what IS are seeing: the US is not actually for real anymore.

Dmitri Orlov described the end of the Soviet Union as the lifting of a dream, a sudden realization that what was ludicrous was in fact powerless as well. How Trump wins is by recognizing this ludicrous unreality in the established “norms” of political behavior. The control system, the “donor class,” the “party [that] decides” are paper tigers, dreams, ridiculous. The US government is on equal footing with Apple- neither could “build a wall” across Mexico, or bomb another state into compliance, or “fix” the economy, and every claim to the contrary is both risible and, most likely, the loss leader for another round of extra-legal exploitation and entrapment. But hey, neither one can keep the bridges from falling down either, or maintain a reasonable life expectancy or low infant mortality rate. Trump is not a fascist or a clown, he simply gives the panopticon no more respect than it can actually command in the real world. Against this, the Clinton and other republican campaigns can manage only a half-throated reassurance that rules and traditions aren’t bankrupt, should matter, and there’s nothing important behind the curtain. Those claims evaporate, USSR-like, with the first throw of a fist.

The Islamic State, the playground killers, Donald Trump, may all be varying degrees of ugly, pointing out varying degrees of failure in the various states they inhabit, but they matter because they’re an indication of something: they are the face of post-surveillance worlds. They are what will replace the failed states we don’t yet realize we live in.